Finding this obvious explanation for my weakness brought me a little strength. I had not had a drop to drink or a bite to eat or a minute of sleep in three days. I thought of sustenance for the first time. At length, as slowly as a caravan of camels crossing a desert, some thoughts came together. I was pinned by weakness to the tarpaulin. And I needed to be higher up if I were to see other lifeboats. My back hurt from leaning against the lifebuoy. My neck was sore from holding up my head and from all the craning I had been doing. I could not stay in the position I was in forever. Only rain, marauding waves of black ocean and the flotsam of tragedy. I looked about for my family, for survivors, for another lifeboat, for anything that might bring me hope. I watched the ship as it disappeared with much burbling and belching. The waves splashed me but did not pull me off. I held on to the oar, I just held on, God only knows why. But I don’t recall that I had a single thought during those first minutes of relative safety.

Had I considered my prospects in the light of reason, I surely would have given up and let go of the oar, hoping that I might drown before being eaten.

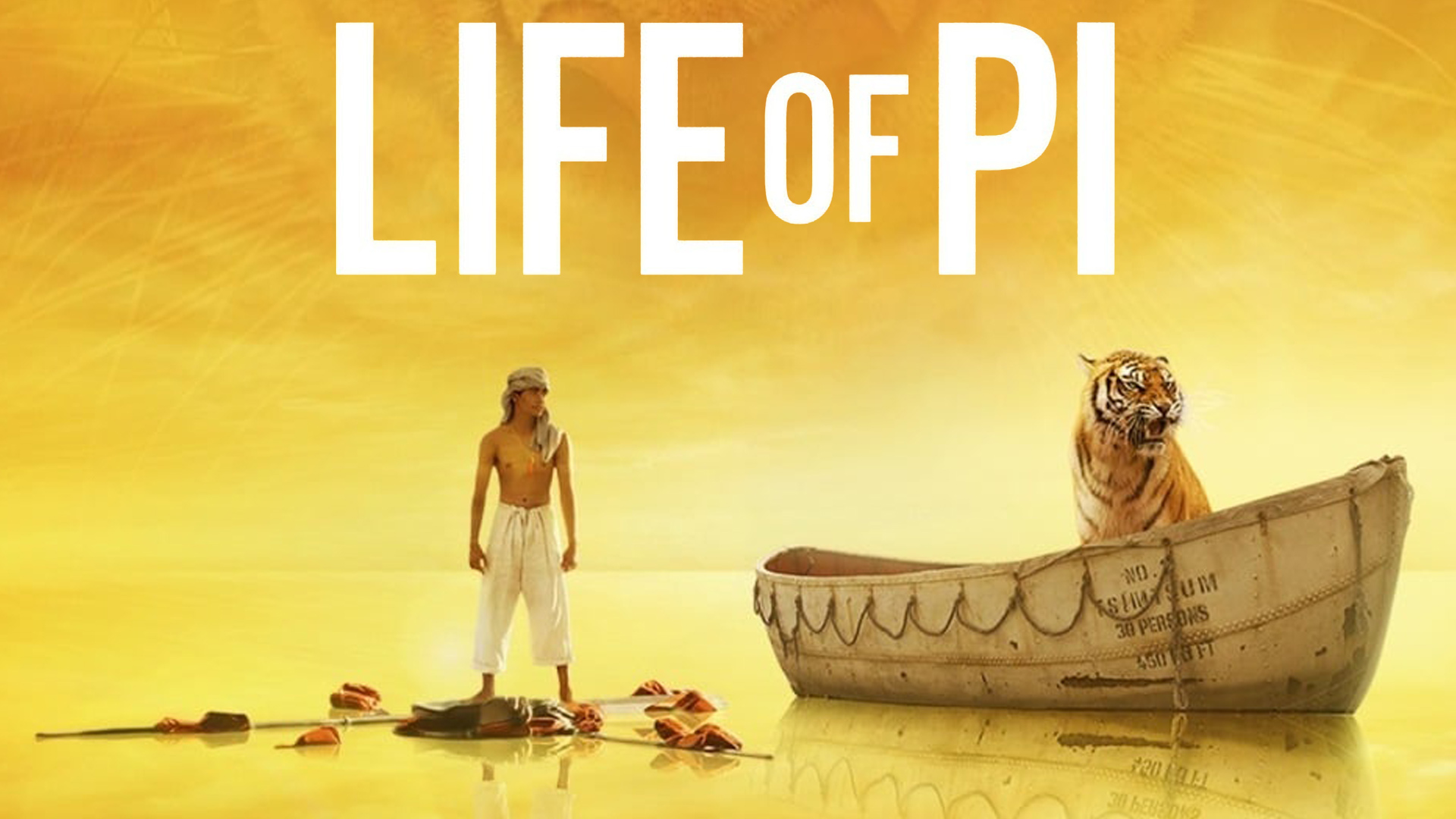

I was alone and orphaned, in the middle of the Pacific, hanging on to an oar, an adult tiger in front of me, sharks beneath me, a storm raging about me.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)